Call it power shifting, packing gears, or side-stepping the clutch. Anyone who has taken a run down the drag strip has tried it, but is it really faster? How much time are you really losing by taking a moment to complete a gearshift smoothly rather than beating the poor life out of your gearbox?

In the road racing community, there are many people who discount what kind of time can be made up by slamming gears. It seems to be understood that shifting gears like a raging hormonal teenager on the racetrack is for immature novices and that it does not make you any faster, or at least not significantly. Okay. Well, let’s investigate.

There are many ways of looking at such a problem, and my preferred way (as always) is to use data analysis to help assist with the problem. But before we delve into the squiggly lines, let’s first introduce a little common sense.

Leaving your foot at full throttle while clutching and “Power Shifting” has the advantage of building up energy during the shift which will be released once the gear is engaged. It’s a great way to break stuff, and a great way to go fast. Any time you have your foot to the floor, your engine is producing every last pony it can. Inversely, any time your foot is not on the throttle, the engine is providing zero horsepower to the wheels. Logically then, any time you are not at full throttle you are no longer accelerating. Therefore, the less time you spend shifting gears, the better.

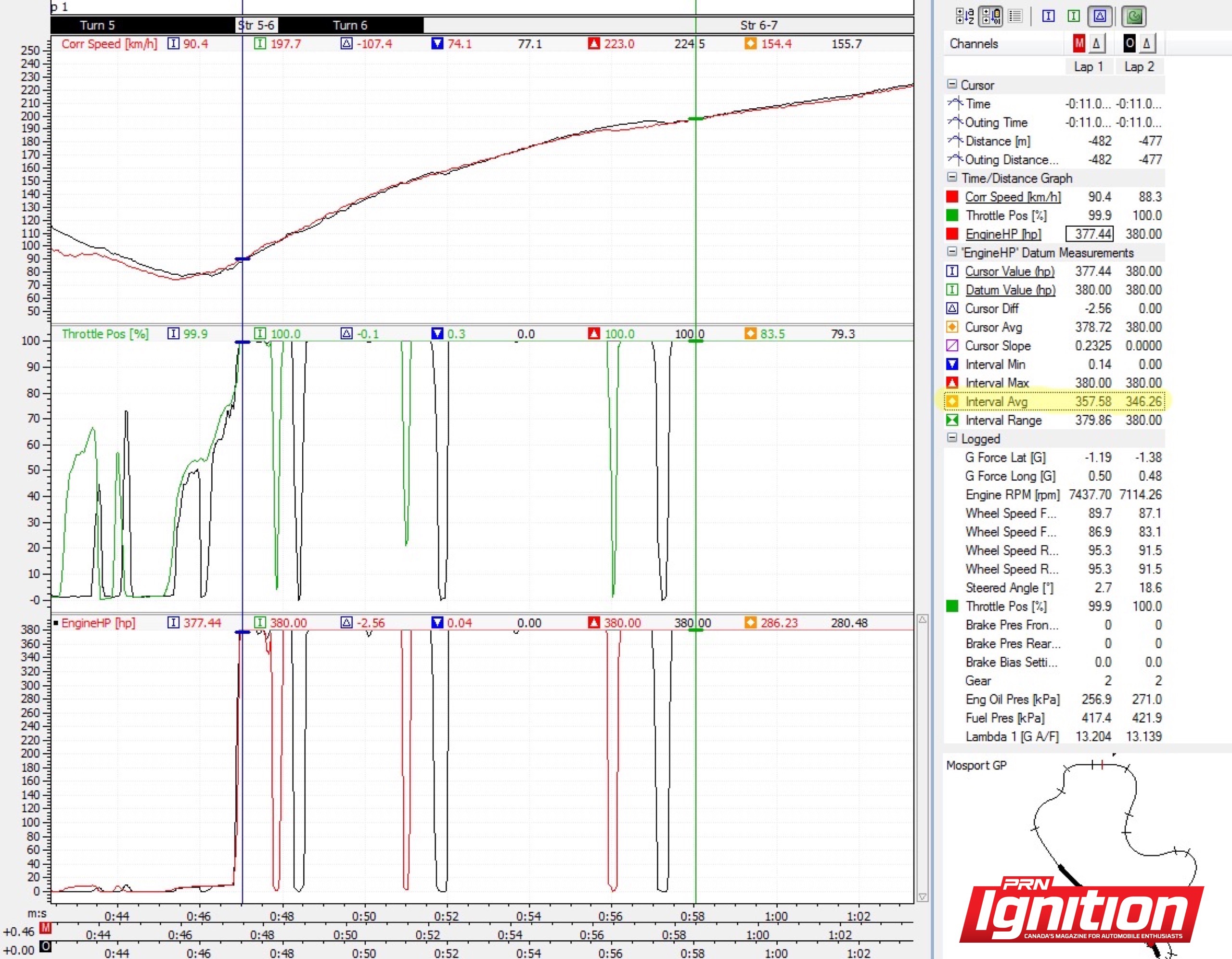

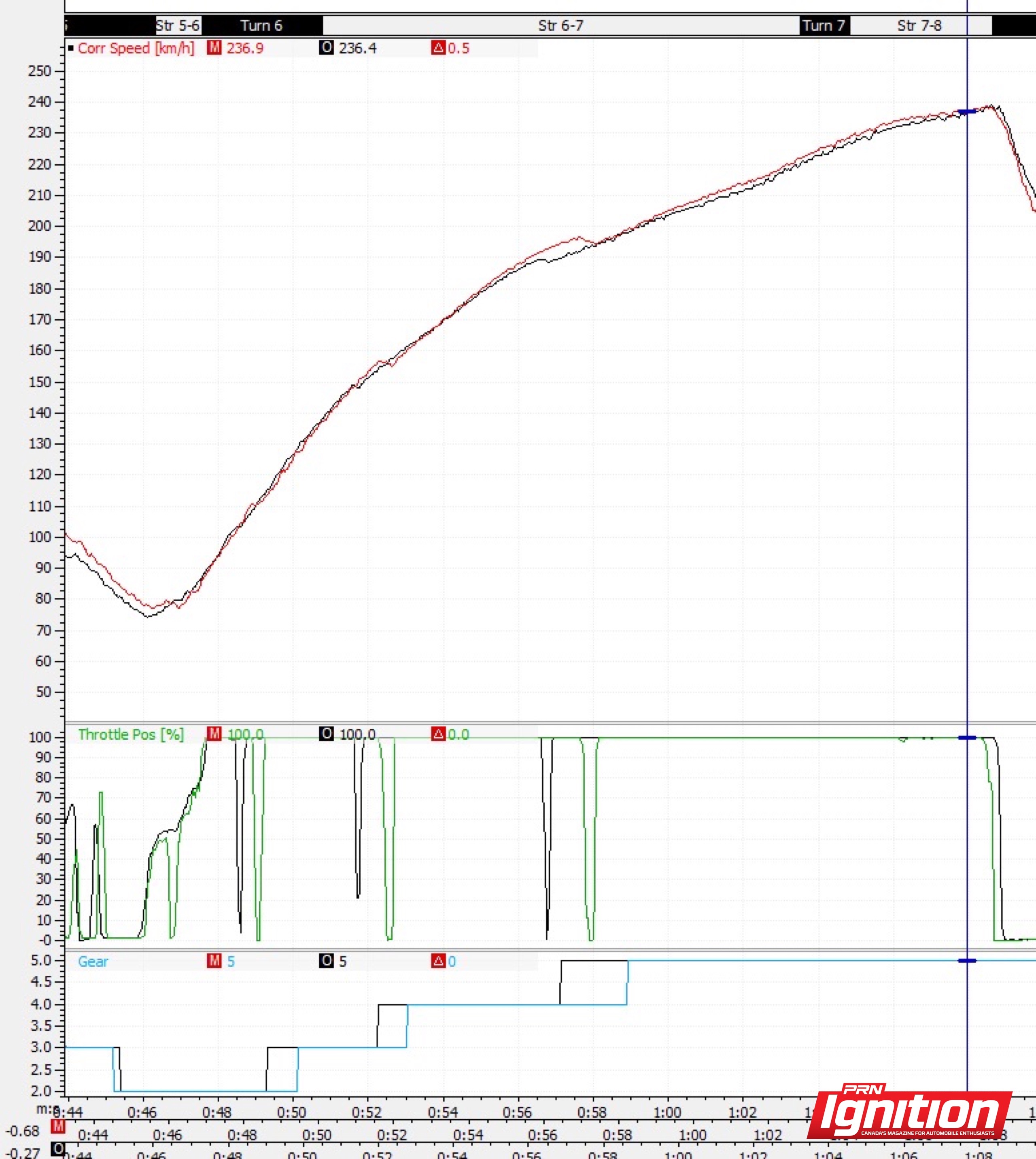

Here is some data that illustrates what we are talking about:

The first image is an example of my personal 350Z racecar climbing the kilometre-long, uphill Andretti straight at CTMP Mosport. The black line indicates an engine with 365 horsepower and a gearbox that can be shifted in 0.25 seconds, and the red line indicates a new, bigger, badder engine with 395 horsepower, but with a clutch drag issue that causes the gear shifts to take significantly longer – up to 0.5 seconds for the fourth to fifth shift. Despite having an additional 30 wheel horsepower, the car was not even one-tenth of a second faster on the back straightaway. If you look closely, you can see that each gear has a steeper slope (the car is accelerating faster), but all gains are lost on the speed that the car loses from drag and the time wasted coasting between shifts. There are some other factors at play, but 30 wheel horses should yield gains of about three- to four-tenths of a second according to other data I have acquired over the years – not 0.7-tenths.

This may have some of you thinking, but let’s use some math to reinforce what we are talking about. For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume the engine has an average output of 380 horsepower since we are not operating at the peak power RPM at all times. If we look at the first 11 seconds of the straightaway and compare the amount of time at full power versus the amount of time at zero power (during the three gear shifts), we can come up with an average horsepower figure.

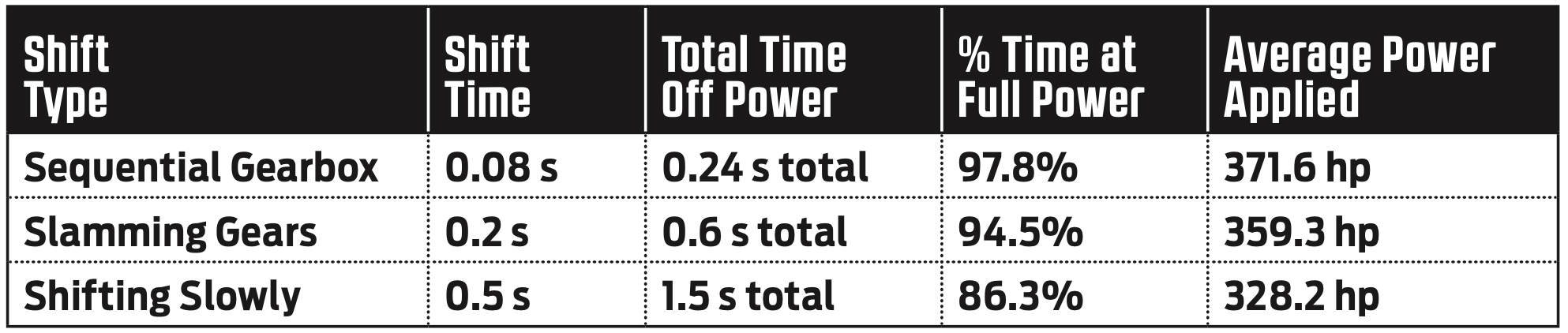

In the chart, we compare the ideal shift time from a sequential gearbox (0.08 seconds, sometimes less) along with the very fast gear shift of a sychromesh transmission (0.2 seconds) and a slow, leisurely shift (0.5 seconds). In the first 11 seconds of acceleration out of a second gear corner, the average power applied to the wheels changes dramatically based on shift time.

Even in the best case scenario, we lose about nine horsepower or 2.2 per cent due to the inevitable fact that you must release power for a long enough period to allow the sequential gearbox to engage the next gear and allow the engine speed to slow down. A very fast shift of a synchro box (to the point where the gearbox is likely being heavily worn out due to the aggressiveness of the shift) loses another 11 horsepower for an average output of 359 horsepower. A slow shift loses a further 30 horsepower of average power applied over that initial 11-second blast out of the corner, down from 380 to 328!

The other thing to note is that losses or gains during the early part of a straightaway (or the first half of the drag strip) are worth more than the last half. This is because the speed lost or gained will carry down the entire straight. A missed shift at the end of a drag race might only cost you a tenth or two, but a mistake at the start will be much more lethal. So a loss of 50 horsepower during the first half of a straightaway due to slow shifts is a sure way to lose some time on the racetrack.

The other thing to note is that losses or gains during the early part of a straightaway (or the first half of the drag strip) are worth more than the last half. This is because the speed lost or gained will carry down the entire straight. A missed shift at the end of a drag race might only cost you a tenth or two, but a mistake at the start will be much more lethal. So a loss of 50 horsepower during the first half of a straightaway due to slow shifts is a sure way to lose some time on the racetrack.

Now, of course, there is some mechanical sympathy required, but the point is that there are real gains to be had from shifting gears as quickly as possible. It does make you faster, and any time you can be faster is time well spent. But drivers beware, because constant hard use can lead to all kinds of broken parts. Use this knowledge to your benefit and consider saving those wild, power shifts for times when they count the most – like qualifying, or when you’re trying to set a new personal best lap.