In the spring of 2012, I visited the atelier that is Singer Vehicle Design for the first time, and the small company was in the throes of ramping up production. To be fair, what Singer does better resembles art than it does production. Those were the days when only sharp Porschephiles were familiar with the work of Singer and the gloriously special Porsche 911s the California shop was turning out.

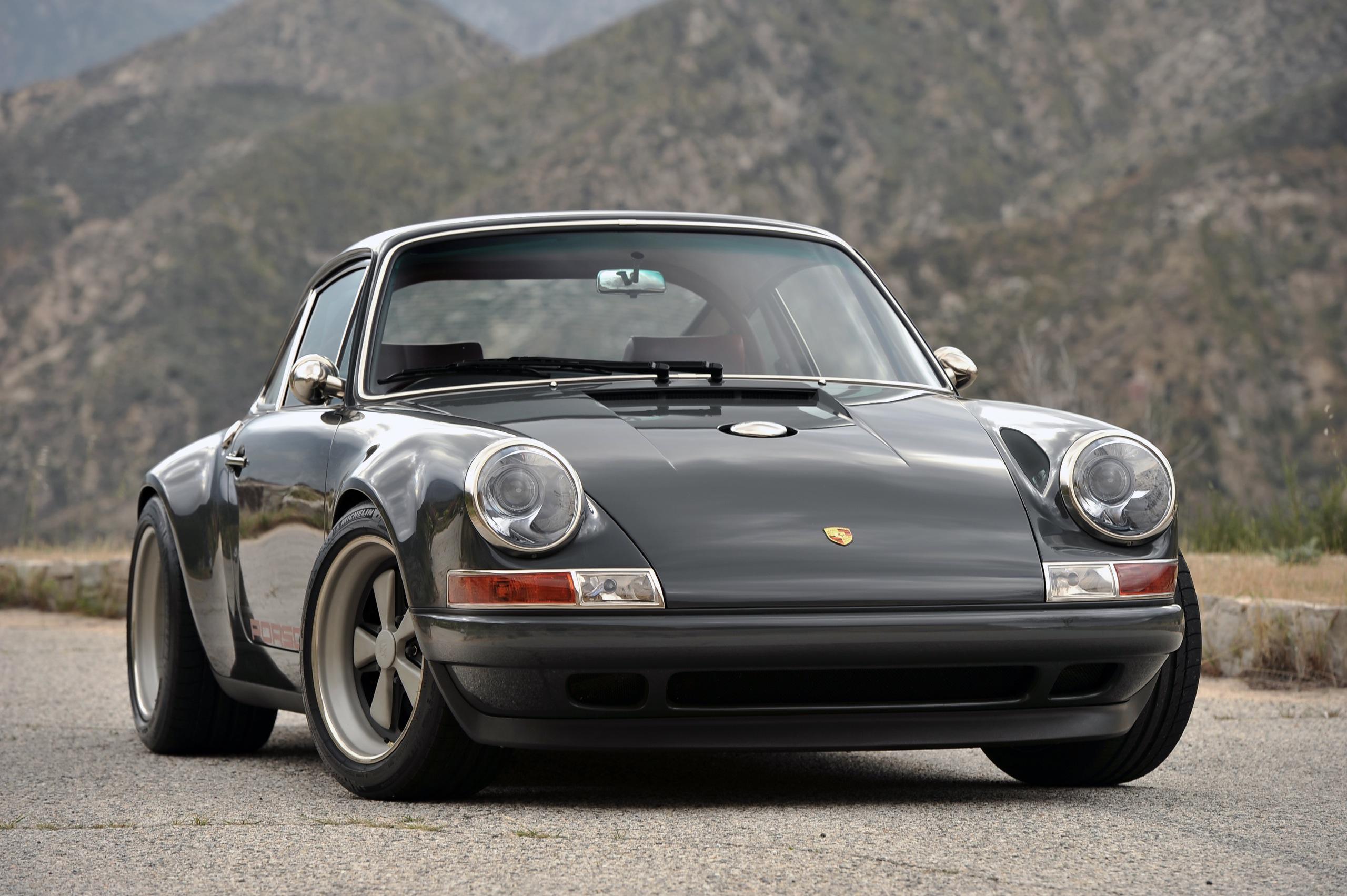

What rolls out of Singer’s doors are Porsche 911s that many people consider to be the finest 911s to ever have graced the earth. Starting with a run of the mill 911 from the early '90s, these are cars that are carefully restored and thoroughly rethought into objects that almost defy description. To the eye, they’re like works of art, but to the driver, they’re simply divine.

The shop was quiet, and technicians were carefully assembling their fourth and fifth cars, while founder Rob Dickinson looked as he’d been working a string 20-hour days for a number of weeks. We sat down for a conversation, but before I could sit, I had to make room by moving boxes of accounting software out of the way.

Dickinson laughed and said, “We’ve got 89 parts suppliers. Making a car is a merry dance of delivery schedules and lead times and madness. It’s actually part of the fun of it, although it’s bloody hard work bringing it all together.”

It’s easy to brush off Singer’s work as just another resto-mod, trendy kind of car, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. Dickinson told me, “It’s meant to honour Porsche design rules and design classicism. It’s meant to not get in the way of a design icon. We’re treading on hallowed ground with this car and we have to be careful. It’s deliberately understated and in the same way Porsche’s development of the 911 was ruthlessly, Teutonicly conservative, incremental changes every two or three years. We respect that. Our car, although being extravagant, respects that Teutonic edge that the 911 has. The car has nobility and has to be respected.”

Before messing around with Zuffenhausen’s finest sports cars, Dickinson’s education and first career was in the car business. “I studied industrial design and car design at college. I went and worked at Lotus and realized I didn’t want to be a car designer,” he said.

He then switched to the family business – the business of rock. “I became a rock musician for 20 years. I was in a band called Catherine Wheel and Canada was our biggest market. We did our biggest shows in Toronto and we played to 5,000 people at our biggest headlining show. We played to more people in Toronto than in bloody London or New York,” Dickinson recalled.

As it turns out, he’s the cousin of another famous Dickinson – Iron Maiden’s lead singer, Bruce Dickinson – and Rob was Catherine Wheel’s lead singer. Which is undoubtedly where the name of the company originated.

With three cars in various stages of assembly, there were none to drive, but I left the shop completely in awe of the craftsmanship of Singer. The 911s that I saw in their shop were unlike any 911 I had seen, vintage or otherwise. The classic and yet athletic aesthetic seems somehow both familiar and contemporary, and attention to detail is at a level simply out of reach of the factory. I left that day feeling unfulfilled.

Fast forward to spring of 2013 and during a trip to L.A., I receive a cryptic email that only asks, “What are you doing Saturday?” Considering the author of that message, there was only one correct answer, so I simply replied, “I am at your disposal,” and for the second time, I make my way to Singer’s shop north of the city.

Dickinson tells me the plan is to drive out to the mountain roads just miles from the shop and then turn me loose in what is a right-hand-drive customer car. The car I’m about to drive is one where the customer has ticked each and every one of the option boxes. It’s got a gorgeous, custom fuel cell under the bonnet, an uprated, bespoke wiring harness (which costs roughly the same as a new Boxster) and bespoke Ohlins shocks. In total, Singer’s services run to $470,000 for this stunning Porsche, not including the cost of the donor car, which must be supplied by the customer.

Looking at this 911, it’s much more compact, in every dimension, than today’s 991 grand tourer. It seems to be no longer than the length of a modern city car and with it’s wider track, its dimensions seem almost square. Behind the wheel, the cabin is smaller, too. It reminds you that you’re driving something of a vintage car and, to a degree, you are. The bones of this car are from two decades ago.

The 911 fires up immediately and there is no mistaking the sound of a classic, highly-tuned, air-cooled Porsche engine. It’s refreshingly raw and honest, and in complete contrast with today’s modern, electronically-nannied engines.

As we take a break on the mountain, Dickinson enlightens me with his 911 ethos. He says, “If an alien came down and knew nothing about the Porsche 911 and saw this, then maybe they’d understand why millions and millions of people like us adore this car.” Looking at this 911, I don’t doubt it.

The chassis of a 911 by Singer is both lightened and optimized with modern suspension engineering. There’s an immediate, direct connection between you and each of the car’s four tires, and the experience is akin to having telekinetic powers. This car listens to your every input and it tells you precisely what it’s doing and what it wants from you. I’ve never driven a car where I’ve felt such deep and immediate confidence. The Ohlins dampers are among the best I’ve come across and do an exceptional job keeping the tires in contact with the road, but also provide a comfortable ride.

I convey this to Dickinson and he tells me, “This is a good compromise – a car which you’d be happy to take to the track, but also to drive to work in the morning. That duality is very important for a 911. It’s very, very easy to turn a 911 into a racing car that you never want to use. And having done that a couple of times myself, you realize that’s not what I want in a car and that’s not what other people want in a car. They want a car that has enough of an amount of visceral thrills but some comfort as well.”

Accelerating through the gears of the six-speed, I revel in the unfettered roar of the flat six. Revs seem to want to climb forever and although there’s no discernible redline on the tach, I shift just past 6,000 rpm in each gear. That’s only because my mechanical sympathy gets the best of me when I remember that the owner of this car hasn’t even driven it yet.

As I’m enjoying the 911, I remark to Dickinson that this car’s size and feel is nothing but perfect. With unreserved confidence, he tells me, “We think the 964 chassis is the high water mark for air cooled 911s. It still has the faithful, 911 rear suspension. It has a sophisticated front end, which allows us to put extremely good damping on the car. It does have one foot in early 911 world, but it does have some of that immediate turn in and steering precision that a 997 GT3 could have as well.” I can’t argue with that and, as an admirer of modern GT3s, I’d even argue that Dickinson’s car steers better than the new ones.

For me, a 911 by Singer is unequivocally the ultimate sports car, let alone the ultimate 911. It’s beautiful, eminently capable and, by virtue of its simplicity and it’s balance, it is confidence inspiring to a degree unheard of in modern cars. To me, this is what makes a 911 by Singer much more desirable than any modern super car.

It’s also got character in spades because Dickinson hasn’t forgotten his roots. In true rock fashion, his tachometers all go to 11.